December tarot reading

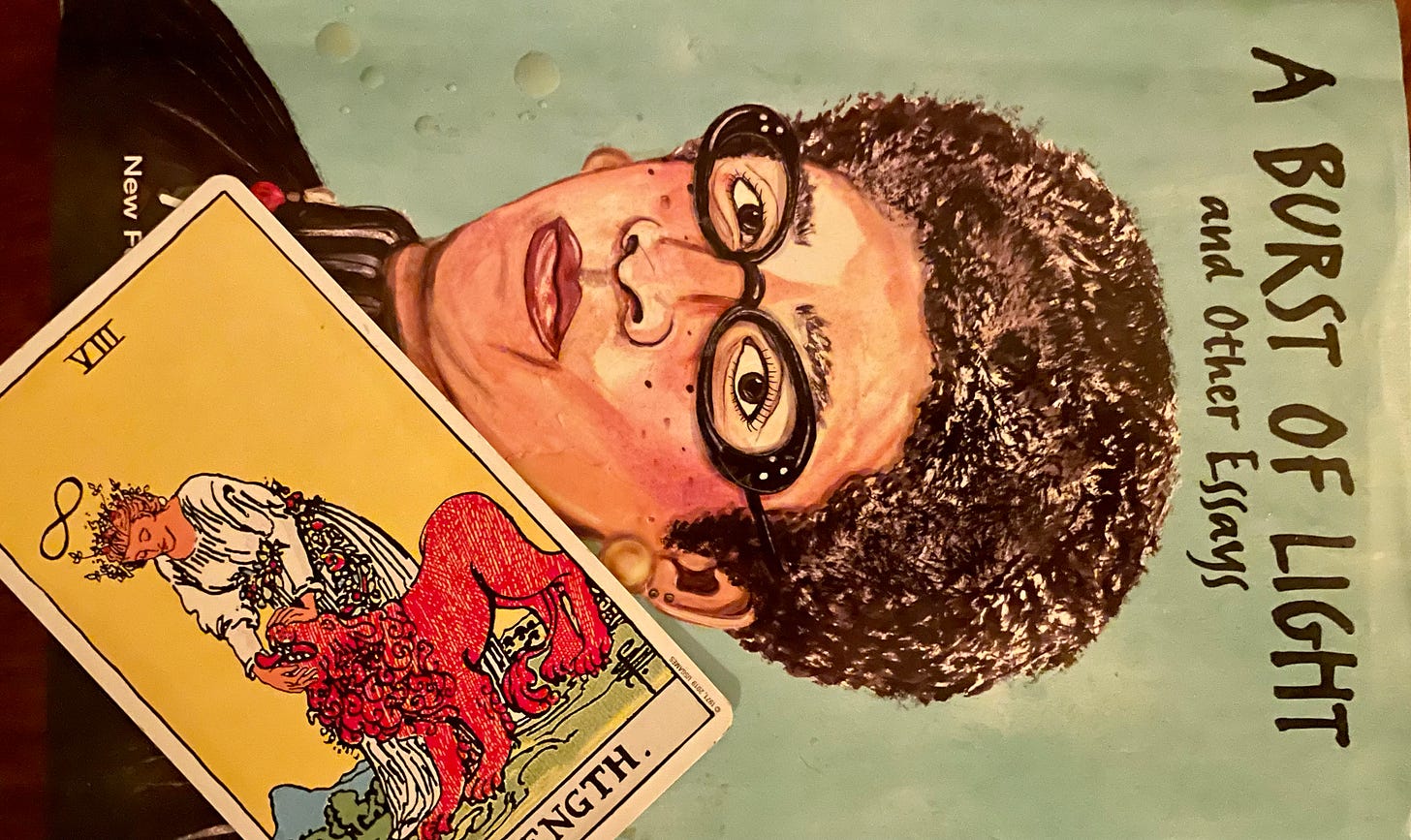

The problem with Strength, Audre Lorde's "A Burst of Light," and bibliomantic 'scopes for the holiday season

The problem with the Strength card is that it’s not good practice to go around looking for conflict in every moment. Conflict is not abuse, Sarah Schulman’s right about that, but neither is it everywhere, all of the time, happening, about to happen,1 only deftly avoided thanks to your brains or dexterity or beauty or very big muscles (or passive aggression.) It’s great to work on your skills for either taming or inflaming when a situation calls for it. It’s great that lady can hang out with that lion on the tarot card without an implement or some chains or even some very big muscles herself.

It’d probably be better if she didn’t feel the need to be in the garden with the lion at all. Let the lion have its space! Appreciate its power and beauty and terribleness with the benefit of a little distance.

Strength is our tarot card for December; so many of my clients recently have been drawing this for their readings. There are questions about the country, questions about relationships, questions about career paths, questions about all three. Associated with Leo, the sign of the Sun where Mars stationed retrograde Friday, Strength is wonderful for shining a light on the dynamics of force and patience—the need for one or the other or an understanding of when and how one is found in the other—wherever conflict, or even just the potential for it, exists. It’s less great at helping you see yourself, steady, at peace, from a distance. The quintessential Leo problem: The sun lights up every corner, but no one really gets a glimpse of the center where it’s own heart lies.

This is not to pick on Leos. We all have this sign somewhere in our charts, and it’s activated for all of us in a big way right now as Mars, the planet of duking it out, sulking alone in a locked room, and risk-taking on a random Tuesday morning with knives and other sharp things you might find in your kitchen, stirs up Leo’s chaotic passions with some unholy backtracking. It’s a bit like that time my friend Jason convinced me to go “cross-country skiing” in the back-country in Montana, which was really just code for nearly breaking my neck on skis that were way too flimsy for the alpine terrain we found ourselves on. I managed the afternoon without killing myself—a fine show of Strength, I must say—but this outing was only a mere six months after I’d had my right wrist and elbow remade with titanium during emergency surgeries after a bike accident.

What little 20-something Cameron needed to learn, in that time of her life, was how to sit her ass down and figure out what she was chasing and why the answer was: adventure that almost certainly guaranteed bodily pain and injury, all as a way to avoid accepting the pain of relationship and career breakups I was experiencing back then.

*

When the doctors tell Audre Lorde that her breast cancer has metastasized to her liver, it takes her more than a full year of running—chasing holy adventure, embroiling herself in noble conflict, causing her body no small amount of pain—before she arrives at an acceptance of her diagnosis and the death that it means is on the horizon.2 Her titular essay in A Burst of Light and Other Essays (1989) centers on these acts of Strength. Written in a series of diary entries that record her initial three years of living with metastatic cancer, Lorde’s first year-and-a-half after diagnosis is a study in trying to negotiate with the lion. It’s full of moving descriptions of her teaching white women in Germany, giving speeches about the Black diaspora in England, and seeking alternative healthcare treatments at a anthroposophist medical facility in Berlin, as she anxiously records the swelling in her belly, her disappeared appetite, the 50 pounds she loses over a course of a few short months.

Finally, after a somber Christmas spent at the Berlin facility, Lorde’s alternative doctors confirm what the oncologists at Memorial Sloane Kettering had told her a year prior in Harlem. Metastasis, months, maybe a year to live. Lorde’s lifestyle doesn’t necessarily change upon receiving this news a second time over, this time from professionals she trusts.3 In a few months, she’ll be in the South of France, meeting with South African women who were essential in the Soweto Uprising against apartheid. In a few years, she’ll be living in St. Croix when Hurricane Hugo hits, and will become instrumental in helping to raise awareness about climate change as she helps the community rebuild.4 She never returns to MSK to resume traditional treatment, opting for her regimen of mistletoe infusions, homeopathy, and changes to lifestyle and diet instead.5 But unlike others who turn to holistic healthcare in the face of mortal disease, she doesn’t flinch away from the material reality of that disease. No longer in denial, she makes her decisions about her health with the full power of her mind, writing poetically about cancer when she needs to fortify her sense of her life’s meaning, writing precisely about cancer when she needs to give herself the benefit of analysis, reason, and distance from her own body.

She keeps going. She lives for seven years with metastatic illness, confounding everyone. “Of course, my oncologist is surprised and puzzled,” she writes on August 12, 1986, after scans showed that the tumors in her liver had both shrunk significantly. “He admits he doesn’t understand what is happening, but it is a mark of his good spirit that he is genuinely pleased for me, nonetheless.”

I don’t have answers about why her metastatic cancer seemed to push itself into remission, especially when others with similar disease prognoses and similar refusals of traditional treatment options—Kathy Acker6 to name one—did not. The lion I myself have to leave alone is the way Lorde’s end-of-life story tantalizes me with the success of non-standard treatments. What is the difference between embracing her final years as a model of true Strength rather than as an illusion of a garden that is not my own to pick from?

A Burst Of Light, though beloved and award-winning, is far from Lorde’s most popular work these days, and when people quote from it, they tend to fixate on passages that reinforce our sense of Lorde as the poet-activist we know and love: the book is filled with sharp analysis and moments of sudden, breathtaking prosody to emphasize the intersecting struggles of Black women, cancer patients, and members of the diasporic and indigenous communities that Lorde worked with around the world. But the book’s center—its glaring heart—reveals a woman whose choices around healthcare in the face of death are tentative, stumbling, kooky, maybe not what we’d expect in our age of “we believe in science” yard signs and post-lockdown rancor about what constitutes good health, evidence-based treatment. It’s uncomfortable to read about her outspoken faith in the unscientific, and, in the first 21 months after her diagnosis, to read about her staunch refusal to acknowledge the reality of her illness.

Eventually, though, she does. She’ll never accept the surgical and chemo recommendations that her oncologist insists upon, but she does accept what that refusal means. She’s in uncharted territory. She holds no silly pretense that being in such an experimental place will mean she defeats death, or even the daily reality of living with painful tumors. She takes her hands out of the lion’s mouth. She stops fighting denial and saves her strength and fortitude for other battles that matter more, other moments of peace that matter more, too. Frequently, she writes, those moments are one and the same:

“Racism. Cancer. In both cases, to win the aggressor must conquer, but the resisters need only survive. How do I define that survival and on whose terms?

So I feel a sense of triumph as I pick up my pen and say yes I am going to write again from the world of cancer and with a different perspective—that of living with cancer in intimate daily relationship.”

Wishing you an end of the year and a start of the New that is triumphant in intimacy with what matters, and distance from what does not.

Below are bibliomantic tarotscopes for the month, using A Burst of Light and Other Essays as inspiration.

The way I do bibliomancy is to use the randomly selected quotations as a provocation to stir up some feeling, or some argument within myself. It’s not about whether I agree with these assertions, it’s more about what does it point me toward that I might need to understand, to develop understanding around? My own suggestions for the month follow the A Burst of Light quote. Read for your rising sign.

Sagittarius Rising: “The night before we part we swim in the pool beneath the sweet evening of the grapevines. ‘We are naked here in this pool now,’ Wassa says softly, ‘and we will be naked here in this pool now.’ We told the women we would carry them in our hearts until we were together again. Everyone is anxious to go back home, despite the fear, despite the uncertainty, despite the dangers. There is work to be done” (103). On the summer solstice in June 2025, you will find a reprieve from the tension of public and private life, of the anxieties of work and home. You will be surrounded by people you love, dressed in flowers. You will have triumphed over something. The way this year is difficult. There is never the hope of totally banishing fear, death, darkness in this life. There is always the hope of moving toward something just like this: a sweet evening beneath the stars and grapevines, a sense of pride in yourself, the fact that love and divinity can be realized here now, and that makes it all OK. Stop fighting shadows! There is work to be done!