Meditation against meditation

The paradox of "the inner life" and thoughts on an active contemplative practice for the anxious and angry among us

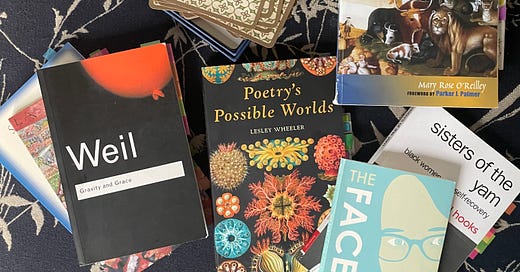

“I know that we don’t have to withdraw from the world to tend to an esoteric fire.” —Mary Rose O’Reilley

“The poem climbs inside you, like a window.” — Lesley Wheeler

I’ve been dreaming of world’s-end hotels. I don’t sleep much, but when I do, the dreams are always nightmares. Sometimes these terrors take the shape of events that happened in real life—the…